Like the perfect sandwich, a perfectly engineered thin film for electronics requires not only the right ingredients, but also just the right thickness of each ingredient in the desired order, down to individual layers of atoms.

Cornell researchers have discovered that sometimes, layer-by-layer atomic assembly – a powerful technology capable of making new materials for electronics – requires some unconventional “sandwich making” techniques.

The team, led by thin-films expert Darrell Schlom, the Herbert Fisk Johnson Professor of Industrial Chemistry in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, describes the trick of growing perfect films of oxides called Ruddlesden-Poppers in Nature Communications Aug. 4.

These oxides are widely studied for their electronically enticing properties, among them superconductivity, magnetoresistance and ferromagnetism. Their layered structure is like a double Big Mac with alternating double and single layers of meat patties – strontium oxide – and bread – titanium oxide – in the case of the Ruddlesden-Poppers studied.

“Our dream is to control these materials with atomic precision,” Schlom said. “We think that controlling interfaces between Ruddlesden-Poppers will lead to exotic and potentially useful, emergent properties.”

Schlom’s lab makes novel thin films with molecular beam epitaxy, a deposition method that controls the order in which atom-thick layers are assembled layer-by-layer, which Schlom likens to precision spray-painting with atoms.

In experiments designed by first author and postdoctoral associate Yuefeng Nie, the researchers found a major difference between assembling atomically precise Ruddlesden-Popper films and the conventional layer-by-layer “sandwich making” of molecular beam epitaxy.

This discovery began when co-author Lena Kourkoutis, then a graduate student and now assistant professor of applied and engineering physics, noticed that sample after sample of Ruddlesden-Popper films spray-painted by Schlom’s lab were missing a layer of strontium oxide.

“Imagine laying down two meat patties on a bun, followed by a layer of bread, and another two meat patties, only to find that the resulting sandwich consists of just one meat patty below the layer of bread and three above it,” Nie explained. “This is the equivalent of what we found to occur with our layers of atoms.”

“After a while we asked, what’s going on?” said co-author David A. Muller, professor of applied and engineering physics. “Where did that first layer go?”

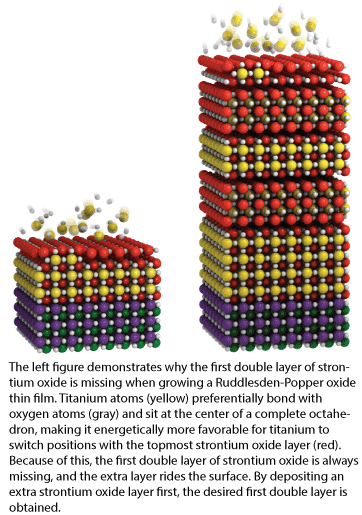

It turned out that following a double layer of strontium and oxygen, the next layer of titanium atoms, instead of sitting on top as expected, seeps down between the two strontium oxide layers. That meant the missing first layer of strontium and oxygen ended up on the film’s surface – a subtlety overlooked for years.

To confirm this, researchers used a combination of techniques, including high-energy electron diffraction, X-ray spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and quantum mechanical calculations.

“This paper is about understanding that this flipping is going on,” Schlom said. “The final sandwich structure is not simply the order in which we lay down the layers.”

The researchers also designed a modification to their crystal growth to make a Ruddlesden-Popper film – this time truly perfect – by laying down an extra layer of strontium oxide to start. Understanding this growth process has helped them make atomically precise and sharp interfaces between Ruddleseden-Poppers, which paves the way for exploring and harnessing their useful properties for devices.

A competing paper by Argonne National Laboratory researcher June Lee, a graduate of Schlom’s group, and published the same week in Nature Materials, arrived at similar conclusions by using different methods.

The Cornell paper, “Atomically Precise Interfaces From Non-Stoichiometric Deposition,” was also co-authored by postdoctoral associate Ye Zhu; graduate students Che-Hui Lee, Julia Mundy, David Baek and Suk Hyun Sung; and Kyle Shen, associate professor of physics and member of the Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science. The work was supported by the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation and the Kavli Institute, of which Muller is co-director.

By Anne Ju, Aug 4, 2014 Cornell Chronicle article (http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/2014/08/perfect-atom-sandwich-requires-extra-layer)